The most frequently asked question that I receive from students from around the world is ‘should I apply to a Caribbean medical school?’. There are plenty of blog posts on the internet that provide advise without objective evidence. So before I give you my unfiltered opinion I want to first present the cold hard facts surrounding the topic as well as some information that is not common knowledge to many pre-med students, most individuals outside of medicine, and future Caribbean graduates. My hope is to arm you with data so that you can make an informed decision about applying to Caribbean medical schools and how best to prepare yourself for success when attending a Caribbean medical school. Before jumping into the benefits and drawbacks of these programs let’s first take a step back and look at the journey of becoming a doctor in the United States.

Part I: Becoming a doctor in the United States

‘What do you call someone who graduates at the bottom of their class in medical school? Unemployed.‘

In order to apply to medical school in the United States you are required, at a minimum, to have completed your pre-med requisite courses which include one year of biology, one year of physics, one year of english, and two years of chemistry (usually general and organic chemistry). Many medical schools are also now requiring molecular genetics and biochemistry. For school specific requirements you can check out the Medical School Admission Requirement website. On top of your pre-med course requirements most American medical schools require a stellar MCAT score, extracurricular activities inside and outside of the medical field, and shadowing experiences of some sort. For the sake of brevity this blog post will not cover the lengthy topic of how to get into medical school.

There are two types of medical schools in the United States- allopathic and osteopathic. Students who graduate from allopathic medical schools earn an ‘M.D.’ which stands for ‘medical doctor‘ and students who graduate from osteopathic medical schools are a ‘D.O.‘ which stands for ‘doctor of osteopathic medicine’. There are differences between the two in certain aspects of their training and the standardized tests they have to take but in clinical practice they are quite synonymous and are otherwise both ‘doctors’ in every modern sense of the word.

In general, medical school in the United States is four years. This includes both MD and DO programs. However to make matters slightly more complicated there are also many medical schools that offer dual MD/PhD programs (generally speaking these are 7 year programs) as well some schools that offer or even require an additional year of research. Other medical schools also offer dual degrees. Some schools offer an MBA or MPH alongside their medical degree. So generally speaking medical school is a four year process but clearly there are exceptions to the rule if you choose to pursue a different path.

After graduating from medical school you are now a doctor, in name at least. In the United States you cannot practice medicine independently without completing residency training. This is worth repeating. In the United States you cannot practice medicine independently without completing residency training. This is the crux of issue regarding Caribbean medical schools. Acceptance into medical school ≠ a job. Acceptance into medical school guarantees you two fancy letters at the end of your name but without landing a residency position you will never practice medicine as a physician. In the remainder of this post I will explain that, based on prior residency match data and from personal experience, by attending a Caribbean medical school you put yourself at a distinct and intrinsic disadvantage in your ability to obtain a residency position in the United States compared with graduates from stateside MD and DO medical schools.

Part II: The Match

‘Like speed-dating but worse’

If we are going to understand why Caribbean medical graduates are at a disadvantage historically compared to American medical graduates we have to first understand the National Resident Matching Program (NRMP), or ‘the match’.

Near the end of the third year of medical school students begin applying for residency. The program known as ERAS, or the electronic residency application system, is the online application students use to apply. It is a common application that almost every residency program uses and makes applying for residency simpler. After uploading your application and appropriate paperwork all you have to do, generally speaking, is click which school you want to apply to.

After the application deadline passes residency programs begin downloading applications. Many programs have hard cut offs. For instance, some programs require you to have a step score above a certain value and if your score is not up to par then your application simply won’t be looked at. Next the residency program picks who to send interview invitations to. Interview season generally lasts 3-4 months from October to January but varies from specialty to specialty. After interview season concludes both students and programs must submit ‘rank lists’. Rank lists are exactly what they sound like. Applicants rank which programs, from the ones they interviewed with, that they want to go to with their most highly sought after program at number 1 and then rank each subsequent program down the line. Programs do the same with applicants. Eventually a computer system attempts to ‘match’ students and programs together to make the best possible fit based on each respective applicant and programs choices. The following video is the best one that I could find that explains this quite complex process as succinctly as possible.

On the Monday of ‘match week’ applicants find out if they have matched or not. They find out where they matched on Friday. The reason for this is that if a student does not match they can participate in the SOAP, or supplemental offer and acceptance program. This is a second chance to try and match into a residency position that went unfilled. More information on the SOAP can be seen at The NRMP website.

This is why medical students ‘match’ into residency spots. It isn’t as simple as a job application. And Caribbean medical students match into residency at a far lower rate compared to their stateside colleagues.

Chapter 3: Raw Data

‘Without data you’re just another person with an opinion’

So now that we kind of understand what it means to ‘match’ into residency let’s finally take a look at the raw data from the 2018 main residency match. The NRMP data is widely available and I encourage you to take a look yourself here. The data describes Caribbean graduates with the term ‘international medical graduates’ or an ‘IMG’. These are further split into two categories: US citizen IMG and non-US citizen IMG. So if you are a US citizen and went to a Caribbean medical school then you are considered a US IMG.

In 2018 there were 37,103 active applicants and 30,232 first year and 2,935 second year residency positions. The following are the match rates for each type of applicant:

- US allopathic graduates (MD’s): 94.3%

- US osteopathic graduates (DO’s): 81.7%

- US IMG: 57.1%

- Non-US IMG: 56.1%

If you only remember one thing from this post then this should be it. Only 57.1% of US IMG’s, or people like me who are US citizen Caribbean medical graduates, match into residency positions versus 94.3% of US allopathic grads and 81.7% of US osteopathic grads. This is terrifying! Imaging going through four years of medical school, accumulate a crushing amount of debt, only to end up without a job or the ability to practice as a physician (check out prior interview posts with individuals who went through that exact experience).

An interesting graph from the NRMP data shows that not every specialty ranks equally.

This graphic shows that the specialty in which the highest percentage of US IMG’s were able to match into was pediatrics at 69.8% of applicants matching while psychiatry on the other hand was the most difficult specialty for US IMG’s to match into at 30%.

So why do Caribbean graduates have a greater difficulty matching? Let’s take a look at NRMP data from a survey of program directors. This survey is also widely available and I encourage you to analyze it yourself here. The survey was sent to 209 program directors (PD’s) and 78 responded, or 37.3%.

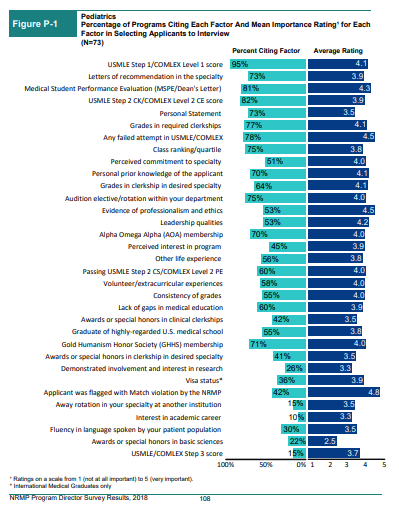

The data shows each individual factor that program directors find important when they choose applicants to interview and rank for residency. As you can see below the USMLE step 1 score, based on this data, is by far the most important factor for choosing applicants to interview.

So a strong STEP 1 or COMLEX 1 score gets your foot in the door but it does not necessarily get you the job. Now let’s use the data from pediatric program directors (PD’s) for the next few graphs. This next graph shows the most important factors that pediatric PD’s felt were the most important factors when ranking applicants.

This graph clearly shows that the more important component of how medical students are ranked on a program’s rank order list is how an applicant interacts with residents and faculty on interview day. Again, a strong USMLE step 1 score seems to be of critical importance in helping get an applicant’s foot in the door but how they interacted on interview day earns medical students the opportunity to walk through it. Of note, each specialty seems to vary slightly in what they rank as most to least important but grossly these trends seem consistent across the board.

The issue however is that getting a stellar USMLE step 1 score isn’t the only obstacle when it comes to matching into residency for Caribbean medical students. At the end of the day all medical students learn the same science but not all medical students have access to the same residency programs.

The same survey of pediatric PD’s (and the same specialty that in 2018 had the highest successful match rate from US IMG’s) shows that some program’s won’t even consider an applicant if they graduated from a Caribbean medical school. The graph below shows that out of the PD’s who responded to the survey only 67% of them typically even interview US IMG’s.

Broken down even more we see that an even smaller percentage of programs will ‘often’ interview and rank candidates from Caribbean medical schools. This is another huge point that you should take away from this blog post.

Again, the match rate for US IMG’s in 2018 was 57.1% versus 94.3% and 81.7% match rate for allopathic and osteopathic grads respectively. I believe that part of that intrinsic disadvantage is that some residency programs simply won’t touch Caribbean medical school graduates. You simply can’t get a job if they won’t interview you for it.

Another unfortunate aspect of being a Caribbean graduate is that it seems to impact the fellowship match too, although to a lesser degree compared to the residency match. If we take a look at the results of the 2019 fellowship match data we can see a clear trend that does not favor Caribbean graduates. The following are the match rates for fellowships in 2019:

- US allopathic graduates (MD’s): 89.4%

- US osteopathic graduates (DO’s): 78.9%

- US IMG: 68.5%

- Non-US IMG: 71.4%

For the sake of brevity I won’t delve too much into this data because the fellowship match is a little bit more complicated and not so clear cut. I’m not certain as to why Caribbean medical graduates have a tougher time matching into fellowships but I am certain that some fellowship programs won’t touch a Caribbean graduate just like how some residency programs don’t.

Chapter 4: Informed Consent

‘Without consent surgery would be considered assault’

In medicine before we perform any test or procedure we are required to get informed consent from our patient. Informed consent is the concept of understanding all of the possible consequences with full knowledge of the possible risks and benefits of said procedure. I think the same should be true about applying to Caribbean medical schools and after getting through all of that data I think we’re closer to fully understanding the implications of attending a Caribbean medical school.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not trying to scare you away from applying. I graduated from a Caribbean medical school, matched into an internal medicine residency program, and successfully matched into a cardiovascular disease fellowship. There are plenty of success stories that originate in the Caribbean and I’ve interviewed nearly a dozen of my colleagues who matched into competitive specialties like emergency medicine and surgery. But Caribbean medical schools aren’t for everyone and you should understand that before you sign up or apply.

Chapter 5: The Caribbean Stigma

‘Some stereotypes originate in truth but are exaggerated by myth’

There is a common misconception in the pre-med community about the ‘Caribbean stigma’. This myth that there would be a doctor or nurse in the hospital you are rotating in that would choose not to work with you because of where you went to medical school. Or that Caribbean medical students are not as qualified as their stateside counterparts. Unfortunately the stigma is steeped in truth.

Caribbean medical students go to the Caribbean because they could not get into a US MD or DO program. That’s why I went to Ross University. I applied to 36 medical schools and Ross University was the only one that accepted me. Caribbean medical schools typically have lower standards and thus not every medical student makes it to graduation. I could not find the statistics on the attrition rate from stateside or Caribbean medical schools but I can speak from experience.

Out of the 440 students who started with me in my first semester of medical school only 76% advanced to their second semester. Although this is only one anecdotal piece of evidence and shouldn’t be used to grossly generalize against all Caribbean schools it does in fact happen. Furthermore, the fact that some Caribbean medical schools are for profit organizations is worrying to me and further underlines the fact that they accept too many students who otherwise wouldn’t be accepted into stateside medical schools. Not to mention that medical school in the Caribbean is just as expensive as medical school in the US. So if you are unable to secure a residency position you will be left with massive loans and a hard road ahead to paying them off.

So although the ‘Caribbean stigma’ exists when applying to and while attending medical school once you make to the hospital nobody cares where you went to med school. In the hospital I’ve met incredibly passionate, intelligent, and competent medical students, residents, fellows, and attending physicians from both Caribbean and allopathic and osteopathic medical schools. I’ve also met terribly incompetent individuals from Caribbean, allopathic, osteopathic medical schools too. Just because you attended a certain medical school doesn’t make you a better or worse doctor. Sure, it certainly impacts your ability to match into residency but there isn’t a single nurse, physician assistant, or doctor out there who will treat you any better or worse just because of what med school you went to.

Chapter 6: The Life of a Caribbean Medical Student

‘It doesn’t really matter where go to medical school because it’s always 72 and fluorescent in the library’

I won’t delve into the specifics of each individual Caribbean medical school and this list is not exhaustive but each of these schools share many similarities with the majority of Caribbean medical schools. In general when you go to a Caribbean med school only the first two years are spent ‘on the island’, or in the actual Caribbean. These first two years are spent in the traditional classroom where we are taught the same basic sciences that allopathic and osteopathic med students learn in preparation for USMLE step 1. It’s really not that bad. I enjoyed my time on the island. I remember being stressed out before my first major exam so I took a stroll on the beach to relax. After leaving the island most medical students rotate in hospitals across the US that each respective medical school has affiliations with. I rotated in hospitals in New York and Florida.

Chapter 7: The End Game

Measure twice, cut once

Your first choice should be to get into a US allopathic or osteopathic program. People who are not accepted at first often work on improving their weak spots in their resumé or work while they study to retake the MCAT. Often students will work a few years, do research, get various master’s degrees, or do a post-baccalaureate degree. Others, like me, don’t want to wait and choose to attend a Caribbean medical school instead.

This is a viable option for certain students but it might not be the right fit for everyone. Some residency specialties, like neurosurgery, orthopedic surgery, ophthalmology, otolaryngology, plastic surgery, urology, and dermatology, are some of the most competitive medical specialties that exist. Even US graduates often have difficultly earning these residency positions (my osteopathic colleague took three attempts to match into derm and he was a PhD too!). By attending a Caribbean medical school you are again giving yourself another uphill battle to fight. So if your heart is truly set on one of these specialties understand that although it is not impossible to match as a US IMG it will make it increasingly more difficult to do so. That being said, if you know you want to go into primary care fields like internal medicine, family medicine, or pediatrics then a Caribbean medical school might be the right fit for you. Again many residency, and fellowship, programs simply won’t look at you because you are a US IMG. So you might not be able to go to an ivy league internal medicine residency or fellowship program but you certainly can still become a doctor.

The ironic part of all of this is that in order to be a good doctor at the end of the day it really doesn’t matter where you went to medical school or what you got on your USMLE step 1 (as this blog post points out). In residency nobody care what your test scores were and when you are an attending your patients won’t care that you went to an ivy league school if you aren’t compassionate, kind, caring, or intelligent. And yet if you don’t do well on your exams, especially coming from the Caribbean, you hurt your chances of ever being able to treat future patients. Whether you like it or not this is the current status quo. So if you go to the Caribbean be ready to work hard, crush your step exams, and get great letters of recommendation.

I hope this post helped uncover some of the hidden curriculum of medical school and residency and didn’t scare you away from applying to Caribbean medical schools. Ross University was the only medical school I was accepted to and they gave me the opportunity to pursue my dream of becoming a physician. It’s up to you to make the best decision for your future career and then make the most of that opportunity. Hopefully now you can do so with confidence and informed consent.

You can also check out my YouTube video on the topic below:

Drop me any follow up questions that you may have below and be sure to subscribe so you don’t miss my next post!